Introduction

The intersection between nutrition and mental health has gained increasing scientific and clinical attention in recent decades. While macronutrients such as proteins, fats, and carbohydrates provide the body with energy and structural components, micronutrients—vitamins and minerals—play critical roles in enzymatic reactions, neurotransmitter synthesis, and cellular protection. Mental health disorders, particularly depression and anxiety, have become leading causes of disability worldwide, affecting millions and imposing heavy social and economic burdens. In this context, understanding the role of micronutrition in emotional regulation offers an important avenue for prevention and treatment strategies.

A growing body of research highlights that deficiencies in key vitamins and minerals may contribute to the onset or worsening of mood disorders. Conversely, adequate intake or supplementation could improve resilience to stress and enhance overall mental well-being. This article explores the biochemical and clinical evidence behind the connection between micronutrition and mood, focusing on specific vitamins and minerals with established or emerging roles in mental health.

We will first examine the physiological pathways through which micronutrients affect the brain, before delving into the impact of B vitamins, minerals, and antioxidant vitamins. Finally, we will consider the application of these findings in clinical practice, discussing both the promises and limitations of micronutritional strategies for mood enhancement. By integrating current evidence, this article seeks to answer a key question: Can vitamins and minerals truly boost your mood?

The Brain–Nutrient Connection: Why Micronutrition Matters

The brain is an organ of exceptional metabolic demand, consuming approximately 20% of the body’s energy despite representing only about 2% of its weight. Micronutrients are indispensable for the enzymatic reactions that maintain neuronal communication, plasticity, and resilience. For instance, vitamins such as B6 and minerals like zinc serve as cofactors in neurotransmitter synthesis, ensuring the production of serotonin, dopamine, and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)—neurochemicals central to mood regulation.

Oxidative stress and inflammation are now recognized as important contributors to depression and anxiety. Excessive free radical production can damage neuronal membranes and impair signaling pathways. Micronutrients with antioxidant properties, such as vitamins C and E, counteract these processes, while minerals like selenium and zinc regulate inflammatory responses. Thus, micronutritional adequacy acts as a protective factor against both biological and psychological stressors.

Epidemiological studies have consistently demonstrated associations between micronutrient deficiencies and mood disturbances. For example, low magnesium intake has been correlated with higher prevalence of depressive symptoms, while iron deficiency has been linked to fatigue, cognitive impairment, and reduced emotional resilience. Clinical trials further suggest that targeted supplementation can alleviate symptoms in certain populations, though results remain mixed due to methodological variability.

Ultimately, the role of micronutrition in mental health reflects a complex interaction between biology, diet, and lifestyle. While deficiencies may predispose individuals to mood disorders, adequate intake supports brain function and emotional stability .

B Vitamins and Emotional Balance

B vitamins, particularly B6 (pyridoxine), B9 (folate), and B12 (cobalamin), are central to one-carbon metabolism, a biochemical network critical for neurotransmitter synthesis and DNA methylation. Deficiencies in these vitamins can impair the production of serotonin and dopamine, leading to mood dysregulation.

One well-studied pathway involves homocysteine metabolism. Elevated homocysteine, a marker of impaired folate and B12 function, has been associated with depression. Clinical evidence suggests that supplementation with folic acid or methylated forms of folate can lower homocysteine and potentially improve depressive symptoms. Vitamin B6, meanwhile, acts as a cofactor for enzymes responsible for synthesizing serotonin and GABA, both of which exert calming effects on the nervous system.

Randomized controlled trials have provided mixed findings. Some show significant reductions in depressive symptoms with B-vitamin supplementation, particularly in populations with pre-existing deficiencies or high homocysteine levels. Others report modest or negligible effects, highlighting the importance of individual variability and baseline nutritional status. Nonetheless, a consistent pattern emerges: adequate B-vitamin intake is essential for maintaining mood stability, and deficiencies increase vulnerability to depression and anxiety.

An important clinical implication is that B vitamins may act synergistically with conventional antidepressant therapies. For example, folate supplementation has been shown to enhance the efficacy of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in some studies, offering a low-risk adjunctive strategy. However, excessive intake, particularly of folic acid, may carry risks, underscoring the need for balanced supplementation under medical guidance .

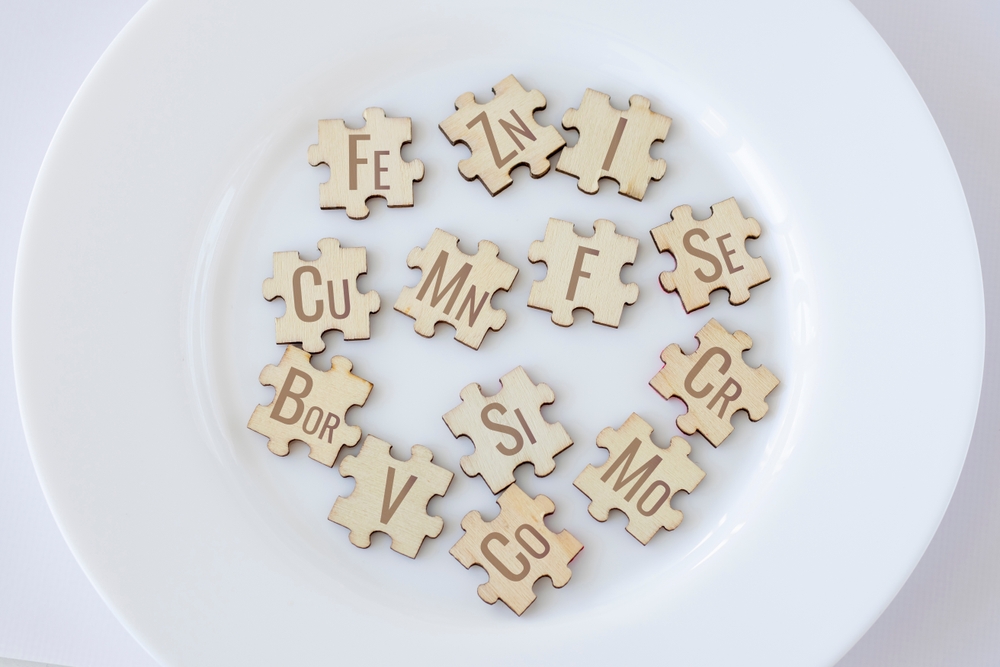

Minerals and Mood Regulation

Minerals are often overshadowed by vitamins in discussions of mental health, yet they are equally vital for emotional balance. Magnesium, in particular, has attracted attention as a natural “relaxation” mineral. It modulates the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, the body’s central stress-response system, and regulates NMDA receptor activity, thereby reducing excitatory neurotransmission linked to anxiety and agitation. Studies have shown that individuals with low dietary magnesium intake are more prone to depressive symptoms, and supplementation may reduce both anxiety and depressive states.

Zinc is another mineral intricately tied to mood regulation. It participates in glutamatergic signaling, neurogenesis, and synaptic plasticity. Deficiency has been observed in patients with major depressive disorder, and zinc supplementation has been reported to improve mood when combined with antidepressants. Its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties further enhance its relevance in psychiatric health.

Iron, although more commonly associated with anemia, also plays a key role in cognitive and emotional functioning. As a cofactor in dopamine and serotonin synthesis, iron deficiency can lead to fatigue, impaired concentration, and mood disturbances. Adolescents and women of reproductive age, in particular, are at heightened risk due to increased physiological demands.

While each mineral exerts unique effects, they also interact with one another. For instance, excessive iron intake may exacerbate oxidative stress, countering the benefits of zinc or magnesium. This highlights the importance of balance and individualized approaches to micronutritional therapy .

Antioxidant Vitamins: C and E as Mood Protectors

The brain is highly vulnerable to oxidative stress due to its high oxygen consumption and lipid-rich environment. Antioxidant vitamins, particularly C and E, provide a line of defense against free radical damage, which is implicated in both mood disorders and neurodegenerative diseases.

Vitamin C plays dual roles: as a potent antioxidant and as a cofactor in enzymatic reactions essential for neurotransmitter synthesis, including norepinephrine and serotonin. Clinical studies suggest that low vitamin C status correlates with increased psychological stress and depressive symptoms, while supplementation can improve mood and reduce fatigue in deficient individuals. Its ability to attenuate cortisol release during stress also adds to its relevance in mental health.

Vitamin E, a fat-soluble antioxidant, protects neuronal membranes from oxidative damage and modulates inflammatory processes. Although less studied than vitamin C in the context of mood, evidence indicates that low vitamin E levels are associated with higher rates of depression and cognitive decline. Supplementation trials show promise, particularly in elderly populations where oxidative stress burden is high.

Together, these vitamins highlight the protective role of antioxidants in mental health. However, large-scale trials remain scarce, and excessive supplementation may be harmful. Thus, a diet rich in fruits, vegetables, and whole foods remains the safest and most effective strategy for ensuring adequate antioxidant intake .

Micronutrition in Clinical Practice: Promise and Challenges

The emerging field of nutritional psychiatry underscores the therapeutic potential of diet and micronutrient supplementation in mental health care. Clinicians increasingly recognize that addressing deficiencies can enhance treatment outcomes, particularly in patients with refractory depression or anxiety. Integrative approaches—combining balanced diet, supplementation, psychotherapy, and pharmacological interventions—offer a comprehensive strategy for managing mood disorders.

Nevertheless, challenges remain. Evidence from randomized controlled trials is often inconsistent, due in part to differences in study design, population characteristics, and supplementation protocols. Placebo effects, while common, do not negate the biological plausibility of micronutritional interventions but complicate the interpretation of results. Moreover, risks of over-supplementation—ranging from gastrointestinal distress to more severe toxicities—necessitate medical supervision.

Another frontier is personalized nutrition. Advances in nutrigenomics suggest that genetic variations influence how individuals metabolize and respond to specific micronutrients. For example, polymorphisms in the MTHFR gene affect folate metabolism and may predispose individuals to depression, raising the possibility of tailored interventions. Future research integrating genetics, diet, and mental health outcomes may enable precision strategies for optimizing mood through micronutrition.

In practice, clinicians should encourage dietary patterns rich in micronutrients—such as the Mediterranean diet—while considering supplementation in cases of confirmed deficiencies. The promise of micronutrition lies not in replacing conventional therapy but in complementing it, offering patients a more holistic and individualized path to mental well-being.

Conclusion

The relationship between micronutrition and mental health underscores the intricate connections between diet, biology, and emotional well-being. Vitamins and minerals play essential roles in neurotransmitter synthesis, oxidative balance, and stress regulation. Evidence suggests that deficiencies in B vitamins, magnesium, zinc, iron, and antioxidant vitamins can contribute to depressive and anxiety symptoms, while adequate intake supports mood stability.

Although supplementation shows promise, especially in deficient populations, it should be approached with caution and under professional supervision. More research is needed to clarify optimal dosages, interactions, and long-term outcomes. As nutritional psychiatry advances, personalized approaches may become central to mental health care.

Ultimately, micronutrition cannot be seen as a panacea but rather as an important piece of the mental health puzzle. A balanced diet, coupled with medical guidance when supplementation is warranted, offers a practical and effective means of supporting both brain health and emotional resilience.

References

Marx, W., Lane, M., Hockey, M., et al. (2021). Diet and depression: Exploring the biological mechanisms of action. Molecular Psychiatry.

Lopresti, A. L. (2019). The role of nutrition in the treatment of depression: A systematic review. Nutrients.

Young, L. M., et al. (2019). The effect of B-vitamins on mood and cognitive function: A review. Nutritional Neuroscience.

Swardfager, W., Herrmann, N., et al. (2013). Zinc in depression: A meta-analysis. Biological Psychiatry.

Grosso, G., et al. (2014). Role of antioxidants in depression and anxiety. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity.